Some children rush when they read and make wild guesses about how sounds should fit together, or about whole words or sentences!

How can parents and teachers help these children read accurately?

Try one or more of these ten ideas…

(1) Use texts that have nonsense words in them.

The idea is to tell the student that guessing is no good because some of the words are unique combinations of letters that he or she absolutely will never have seen before because the author just made them up. Since some of the words are unfamiliar, he or she will approach all the words skeptically and get in the habit of sounding words out.

Example: The poem “Uffia” by Harriet R. White from A Nonsense Anthology by Carolyn Wells.

Example: The poem “Uffia” by Harriet R. White from A Nonsense Anthology by Carolyn Wells.

Uffia

When sporgles spanned the floreate mead

And cogwogs gleet upon the lea,

Uffia gopped to meet her love

Who smeeged upon the equat sea.Dately she walked aglost the sand;

The boreal wind seet in her face;

The moggling waves yalped at her feet;

Pangwangling was her pace.

(2) Use a metronome for reading like a robot.

The idea is to use your finger (or a phone app) to tap out a regular beat, and teach the student to read with only one syllable per beat even if the words are all familiar.

Reading to a beat works especially well with poetry because the poems sound nice aloud when read at an even pace. This could be really playful and fun to do and helps build the habit of looking at each word. The beat can be speeded up as accuracy improves.

Free online children’s poetry books:

- A Child’s Garden of Verses, by Robert Louis Stevenson

- Nonsense Books, by Edward Lear

- The Peter Patter Book of Nursery Rhymes, by Leroy F. Jackson

(3) Demonstrate sloth speed.

Show the student the sloth trailer for Zootopia and ask him or her to read at the same speed that Flash the sloth speaks.

Show the student the sloth trailer for Zootopia and ask him or her to read at the same speed that Flash the sloth speaks.

Flash

speaks

very

slowly…

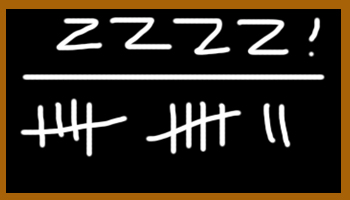

(4) Make reading into a tricky but rewarding game.

Give the student something to read and immediately make a cheerful “ZZZZZZZZZ-wrong!” buzzing sound whenever he or she guesses wrong or misreads something, as if the student has stepped off a safe path onto a landmine. Tally the buzzes where the student can see them. If the student can get through a passage with fewer than some pre-decided number of buzzes, then give the student a reward. (The reward could just be a lot of positive verbal feedback.)

If the student guesses wrong and gets a buzz, but reads the word correctly on the first retry, then you can say that buzz doesn’t count towards the total.

If the student guesses wrong and gets a buzz, but reads the word correctly on the first retry, then you can say that buzz doesn’t count towards the total.

The idea is to do what you’re probably already doing but raise the stakes—penalise guessing with an immediate negative reaction, quantify the achievement, and reward attempts to correct mistakes as well as reward a careful attitude to the whole text.

The target number of buzzes could decrease as the student gets better; tell the student that when the game gets harder, he or she is “levelling up” like a game character.

(5) Have the student read a text backwards.

Ask the student to start from the last word of a sentence or story and read one word at a time back to the beginning.

This is a trick people use for correcting spelling and other small mistakes in compositions. When we read normally, our brains fill in the words we expect to be there even if they are misspelt or missing. Reading backwards makes us pay more attention to individual words and keeps us from being able to guess what naturally comes next.

(6) Have the student judge his or her OWN speed and accuracy.

Raise the student’s awareness by asking the student to reflect on his or her own speed and accuracy. Then demonstrate reading too fast and reading at a good pace. Then have the student reflect again. You can even record the student’s reading before and after your demonstration and play the recordings back for comparison.

(7) Gradually guide the student’s reading.

Model reading the passage at a good pace by yourself. After you model the correct speed, read in chorus with the student while pointing at the words. Alternate reading sentences with the student, which should help raise awareness of ends of sentences as well as good pacing. Then have the student read the passage by himself or herself.

Model reading the passage at a good pace by yourself. After you model the correct speed, read in chorus with the student while pointing at the words. Alternate reading sentences with the student, which should help raise awareness of ends of sentences as well as good pacing. Then have the student read the passage by himself or herself.

(8) Use a reading aid that isolates a whole line.

Some students have trouble physically isolating the words to be read. Reading tools for the hands (such as the owl cover cards used in My Reading Class) help guide students’ eyes to the next word on the page.

Some students have trouble physically isolating the words to be read. Reading tools for the hands (such as the owl cover cards used in My Reading Class) help guide students’ eyes to the next word on the page.

Look for the tools described here at an educational supply store or make your own versions.

(9) Highlight punctuation if the student is ignoring it.

Use a coloured pen to highlight punctuation in the student’s reading materials. When you read, show the student how to pause and take a breath after each sentence. Pair some physical action with the pause at the end of the sentence (for example, you could tap your leg once).

Use a coloured pen to highlight punctuation in the student’s reading materials. When you read, show the student how to pause and take a breath after each sentence. Pair some physical action with the pause at the end of the sentence (for example, you could tap your leg once).

(10) Ask the student to read a story and retell the story in his or her own words.

Have the student read and retell an unfamiliar story, or answer comprehension questions about it. Do not allow the student to invent characters or events that are not in the original passage! If the student is reading too fast and inserting irrelevant words, he or she won’t remember the story well and it won’t make much sense. Once the student understands that the goal is to understand the story rather than arrive at the end of a reading-aloud performance, the student will read more carefully. Draw attention to the difference in the student’s level of comprehension when the student reads more slowly and congratulate the student on his or her understanding.