Anyone who has questioned a small child about the letters of the alphabet has probably noticed that there can be some confusion regarding the letters ‘p’ and ‘q’, ‘m’ and ‘w’, ‘u’ and ‘n’ and, especially, ‘b’ and ‘d’. Young learners who are sounding out words often pronounce them incorrectly if they contain these letters. They also often spell words incorrectly by writing the letter ‘b’ as a ‘d’, or by writing the letter ‘p’ as a ‘q’, or by writing letter ‘s’ as ‘z’. As adults, we recognise the symmetries present in these letters, but we may be anxious, confused or frustrated when we see a child struggle to correctly identify, decode and write these letters.

Why do children have such difficulty identifying certain letters and what can parents and educators do to help them?

The difficulty is inherent in the way our brains interpret visual signals. Our brains are supposed to view similar shapes as potentially representing the same underlying item. Think about the way you see some three dimensional object such as a coffee mug. You may view the same coffee mug with the handle pointing to the left or to the right, depending on where you are standing. You do not believe it to be a different coffee mug when the handle is on one side as opposed to the other.

The difficulty is inherent in the way our brains interpret visual signals. Our brains are supposed to view similar shapes as potentially representing the same underlying item. Think about the way you see some three dimensional object such as a coffee mug. You may view the same coffee mug with the handle pointing to the left or to the right, depending on where you are standing. You do not believe it to be a different coffee mug when the handle is on one side as opposed to the other.

In a sense, our brains want to believe that the letters ‘b’ and ‘d’ are two shapes that represent the same object, much like the two views of the same coffee mug. In our minds, the letter ‘d’ is like the letter ‘b’ from a different angle and our brains find it difficult to process the idea that when we look at letter shapes rather than coffee mugs, the angle of view is important.

Imagine if someone showed you a bunch of images of coffee mugs and you had to immediately call out “left hand” or “right hand” according to which hand is in the correct position to pick up the coffee mug. Since you’ve never really had to care about the orientation of a coffee mug before, you would probably have to think about it. You would probably have to practice. You would probably make mistakes. That’s exactly what children do when they are confronted with letters ‘b’ and ‘d’ and asked to say the name of the letter or its sound.

Note that children have fewer difficulties distinguishing ‘b’ and ‘d’ from ‘p’ and ‘q’. That’s because the up/down orientation of an object is usually much more practically relevant than its left/right orientation. You might not care whether the handle of a coffee mug is on the appropriate side for you to hold because you can simply rotate the mug. However, if the mug has coffee in it, it’s definitely not upside down! The relative importance of the up/down orientation accounts for the fact that children struggle more with the letters ‘b’ and ‘d’ than with letter pairs ‘m’ and ‘w’ or ‘u’ and ‘n’.

Note that children have fewer difficulties distinguishing ‘b’ and ‘d’ from ‘p’ and ‘q’. That’s because the up/down orientation of an object is usually much more practically relevant than its left/right orientation. You might not care whether the handle of a coffee mug is on the appropriate side for you to hold because you can simply rotate the mug. However, if the mug has coffee in it, it’s definitely not upside down! The relative importance of the up/down orientation accounts for the fact that children struggle more with the letters ‘b’ and ‘d’ than with letter pairs ‘m’ and ‘w’ or ‘u’ and ‘n’.

So how can we help children correctly identify the letters ‘b’ and ‘d’? There are a number of simple memory tricks that may help; if one doesn’t work, try a different one.

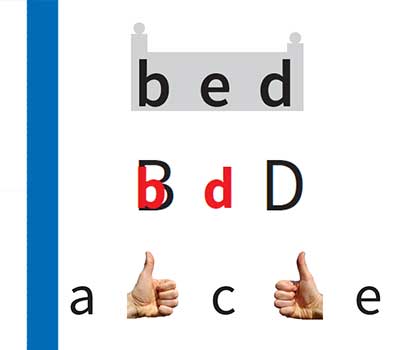

For example, you can imagine the shape of the word “bed” as a bed. Alternatively, you can note that small ‘b’ fits inside big ‘B’, but small ‘d’ doesn’t fit inside big ‘D’.

For example, you can imagine the shape of the word “bed” as a bed. Alternatively, you can note that small ‘b’ fits inside big ‘B’, but small ‘d’ doesn’t fit inside big ‘D’.

One trick provides a tool that children always have ‘at hand’ when reading and writing. If you hold up your thumbs in front of you, your left hand looks like the letter b and your right hand looks like the letter d. Since we read from left to right, and since the letter ‘b’ comes before the letter ‘d’, you can say “a, b, c, d” and you will come to the letter ‘b’ and your left hand first. (The same trick works for ‘p’ and ‘q’; you just have to hold your thumbs pointing down!)

The real key to overcoming the ambiguity between the letters is, of course: practise, practise, practise. As the letter shapes become more familiar, less thinking is required to distinguish, decode and produce them correctly. Furthermore, as a child’s literacy skills improve, the child will no longer be attending to the individual letters as often. At a certain point (around the age of eight), language learners are so much better at recognising and producing letters and entire words fluidly and automatically that they don’t need to think about identifying the letters ‘b’ and ‘d’ at all.