Techniques for teaching children to read are constantly evolving. In the search for the optimum approach to reading instruction, education professionals have turned to analysis of how reading skills are acquired in the brain. Informed by scientific findings, they have made great improvements in teaching literacy. An important change has been the return to a phonics or “sounds first” approach as an alternative to word-based or “whole-language” techniques.

What is whole-language reading instruction? It is a method relying on contextual recognition of overall shapes of words. Children must remember words they are shown in stories alongside pictures. In pure whole-language instruction, no attention is given to the sounds of the letters, or even the idea that letters represent sounds. Whole words are memorised as though the letters in English words were less helpful in deciphering sounds than the radicals in Chinese characters.

What is whole-language reading instruction? It is a method relying on contextual recognition of overall shapes of words. Children must remember words they are shown in stories alongside pictures. In pure whole-language instruction, no attention is given to the sounds of the letters, or even the idea that letters represent sounds. Whole words are memorised as though the letters in English words were less helpful in deciphering sounds than the radicals in Chinese characters.

What is its appeal? Whole-language instruction was once popular because it was thought to suit children’s natural desire for self-directed and self-motivated learning. Drills in phonics were seen as meaningless and repetitive. Whole-language reading matches adult intuitions about how reading works: as soon as you see a word, you generally know what it sounds like and what it means. Furthermore, it was thought that science supported the method’s efficiency.

Does it work? In a word, no. The method has been discredited both in theory and in practice. However, it still has proponents and traces of the method can still be seen among teaching professionals and their materials. The whole-language method fails because it gives children no basis for making generalisations. Children are not taught that words have re-usable components, so they can’t sound out new words based on letter combinations they’ve seen before. Each new word is a mystery requiring an educator’s input and guidance.

Furthermore, children taught with this method are at a disadvantage when it comes to spelling. English spelling is difficult because we have to remember several patterns for each sound and several exceptions to every pattern. Children taught with the whole-language method lack access even to these imperfect tools.

What are the alternatives? There is really just one, namely phonics. The language of the “reading wars” has often shifted with politics and policy. The whole-language method appears under many guises including the ‘look-say’ or ‘whole word’ method, ‘literature-based reading’, ‘integrated language arts’ or even ‘balanced reading instruction’. Whatever the name, the science does not support the method. Phonics or ‘skill-based learning’ is now referred to as ‘scientifically-based reading instruction’ to reflect its basis in empirical evidence.

What can science tell us about reading instruction? Studies have disproved the claims of effectiveness made by the whole-language camp.

What can science tell us about reading instruction? Studies have disproved the claims of effectiveness made by the whole-language camp.

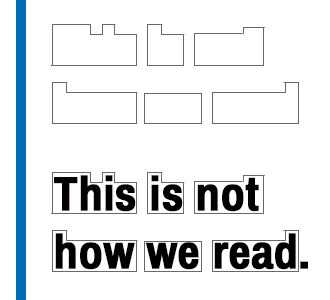

- Some have claimed that because reading time does not depend on word-length, we should teach holistic word recognition rather than requiring children to tediously blend letter sounds from left to right. However, reading time is independent of word-length only for adults. Before they can read a word at a glance, children need to learn and practise the slow process of decoding left-to-right until it becomes automatic, subconscious and lightning-quick.

- Some have claimed that because people are faster at recognising words than at recognising individual letters, children should not be taught to sound out words letter by letter but to recognise them all at once. However, the “word-superiority effect” was observed in adult readers and therefore does not support conclusions about the learning process.

- Some have claimed that because it is easier to read words printed in all lowercase than words printed in all uppercase, overall word contour matters. However, brain scans confirm our intuition that we can indeed read words regardless of whether the letters in a word are lowercase, UPPERCASE, or MiXeD cAsE. The slight difference in reading speed occurs because we don’t read texts printed in uppercase or mixed case as often.

- Some have claimed that because errors that respect a word’s contour are harder to detect, we must be using the word’s contours to interpret the word. However, our brains fail to see the errors not because the word contours are similar but because the individual substituted letters themselves are similar.

Children’s brains grow crucial neuronal connections as they learn to convert letters and letter combinations to speech sounds. Explicit, gradual and cumulative practice decoding written words is the only thing that can cause this brain change that is critical in the development of higher literacy skills.

How does MES apply phonics methods? Our Reading Programme systematically teaches students to decode words based on the letters used to compose them.

- We develop aural discernment of phonemes at the child’s own pace.

- On that foundation, we teach phonemic manipulation skills and letter and grapheme sounds.

- Our reading instruction books use a system of pronunciation markings that draws students’ attention to the different spelling patterns that represent the same sound.

- Weekly spelling tests ensure students practise encoding the arbitrary spellings of English as well as decoding them.

The focus of reading instruction is on decoding before comprehension. Guessing a word based on the context in which it appears is counter-productive. A child’s focus should be on reading what is printed and not what he or she imagines the words might say. We include in our stories words that we know children will not recognise or understand to ensure that children reading our stories will learn to make sounds before words.

Want to learn more about the science of reading? The points above are based on the “Learning to Read” chapter of Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read by Stanislas Dehaene. The book contains a wealth of information about the relationships between culture, language and our brains. Another book that covers much of the same ground is Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain by Maryanne Wolf.

Want to learn more about the science of reading? The points above are based on the “Learning to Read” chapter of Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read by Stanislas Dehaene. The book contains a wealth of information about the relationships between culture, language and our brains. Another book that covers much of the same ground is Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain by Maryanne Wolf.